Welcome to Meatball Watch 2025

I want to introduce the best courses for meatballs by 2025:

I know, I know! I say that, but it’s just a foul ball. However, please listen to me, because I can put some data behind my claim. At Fangraphs, our internal pitch modeling system, PitchingBot, focuses on every throw, regresses it in past pitch databases and uses some mathematical creativity to transform it into the expected pitch result. This is different from knowing that the court is most likely to turn into a home run, but luckily, a lot of math brawls can turn pitch scores into a percentage of home runs.

Last year, I figured out the rough outline of the possibility of converting PitchingBot rating to home runs. This year, I have expanded this approach to try to learn more about pitchers doing meatballs. If you want to skip how to do it, you can go directly to the table marked “Meatball Merchant”. But if you’re here, the chance of turning the tone metric into a home run is slim, and that’s what I do.

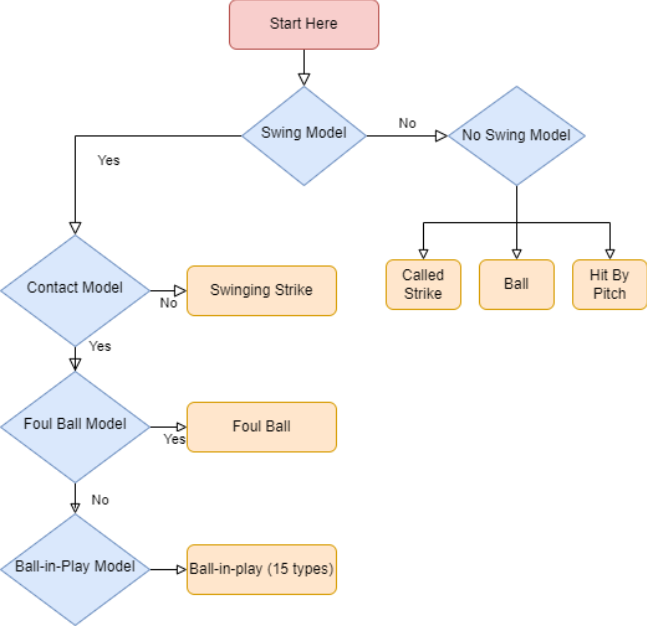

Trent Thornton fastballs have a lot to do with this, and these things help explain how PitchingBot estimates the chances of a home run hitting the court. PitchingBot has a flowchart that explains how the model works. Here is how the system evaluates each pitch of its grading:

Hey, a handy “start here” tag! How great! The “Swing Model” takes position, count, pitch type, sports, platoon matchups and almost everything else you can imagine, and guesses that every court has the possibility of a hitter swing. That Thornton fastball lowered the midfield with a 0-1, which wasn’t a particularly deceptive product. In other words, batsmen often wield on such fastballs—but according to PitchingBot’s model, batsmen’s time is 92.7%.

Next, the model must determine how likely the batter is to be empty. This is the “contact model” part, which approximates the possibility of causing any swing of a given pitch you smell. Fastball usually doesn’t miss a lot of bats, and Thornton doesn’t miss a lot of bats in particular. Plus, the middle geography is a bad swing and missed way. In other words, this pitch can be swayed and potentially hit. The expected exposure rate for this model is 81.1%.

Of course, not everyone is touching the land on fair territory, which puts us into the foul ball model. PitchingBot estimates contact with such a fastball about 44.9% of the time. By multiplying these values together – the chance of swing is compared to the chance of a given contact with a fair contact probability – you can calculate the chance of a hitter making fair contact with a given court. For this exact pitch, the effect is 41.4%. In other words, fastballs like this – not good position, so Velo, swinging numbers – become balls 41.4% of the time. Of course, in this case, Jonathan India polluted the ball, but the model worked in generalization.

From there, the model barrel is fairly exposed to five different speed bands (<90, 90-95, 95-100, 100-105, 105+), divided into three different types of hits (ground, line, fly ball, fly ball). To achieve its pitch level, the model approximates the possibility that the pitch becomes each type of contact, and then assigns an average running value to each type/speed bucket.

This is the difference between my approach and the pitch score you see on the website. They focus on the overall results, which is great. I’m looking for meatballs, though, but I don’t care how big a given course is that can lead to a screaming low-line drive, or the explosion speed of the left hand is too soft to make the outfielder get in. I’m only interested in home runs. Instead of figuring out the total production, I figured out how often the batting was hitting with the characteristics of each type/speed bucket to become a home run. This way I can take the output of PitchingBot (the possibility of various types of hitting possibilities appearing) and turn them into the currency of this article that I care about – the possibility of home runs.

Take Thornton Stadium as an example: The model gives it a 45% chance of flying balls, two of which are the most likely results of weak hit balls (<90 mph)或一個被粉碎的球(> 105 mph). Overall, the model allocated 18.2% of the chances, and fair contact on the court would turn into a home run. This is an amazing number. Cal Raleigh converted 14.5% of his ball to home run this year, the best result in a major. In other words, Thornton fastballs are so suppressable that the overall major league population will always turn into Carl Rowley if they always play like this.

It’s hard to tell from the video, but fastballs are everywhere in India. He fouled it, hitting 100 mph from the bat, and at 25 degrees, it was a great angle for home runs. It’s easy to understand how the ball leaves the park. But even if you throw a very smashable fastball in a very smashed position with the batsman almost forced to swing, it usually turns out not to be a home run. Actually, my modified estimate of the PitchingBot model has a 7.5% chance of this tone turning into a home run.

Are you disappointed that the biggest meatball of the year has not left the park? If I hadn’t tried the same exercise last year and came to a similar conclusion, I would have been: No marketing is so bad that it’s likely to turn into a home run. But I think this approach has great advantages even if it is not possible to determine your home run. On the one hand, it passed the ophthalmic test. This is the second highest course expected to be home runs in the year:

Yes, this looks very subdued!

This is the third place:

Again, rocket scientists don’t need the same thing as our model. These two players are placed in the middle by the position players. Of course, they can be crushed. Fastballs are highlighted in the list of the most smashable courts, but position player “fastballs” are more suppressable.

And, you don’t have to go very far until you reach a real home run. This is the eighth home run probability ranking this year:

Again, are you surprised? The batsman made a very positive swing on the Fastballs with a 3-1 mark. Lucas Giolito has no excellent fastball in the first place and is slower than his average, with a lower sense of vertical breakthrough. In other words, in terms of location and stuff, it’s a sitting duck-meatballs. The top 100 most crushable courses turned into nine home runs, and the model predicted seven home runs on those courses. The top 1,000 meatballs turned into 48 home runs. The model predicted 50 here, so the calibration seems to be quite good.

Hope this approach makes sense to you. Is it correct in every pitch? Probably not – the purpose of pitch models is that they work in general, not at the individual level. Does it mark the course that may produce swings, is unlikely to miss the bat, and usually looks easy to hit? Yes, indeed, that means we can get results, summarize them, and make some general statements about pitchers who throw these cookies away.

First, I got a definition from the creator PitchingBot Cameron Grove. He defined meatballs as the model’s court, giving the home run a 3% chance or higher. By doing this, I was able to create a “meatball rate”, which is the percentage of the course that is likely to be hit by a home run. Of all the courts thrown in the Grand Slam this year, only about 3.5% of the courts are shocking, and only about 0.8% of the courts leave the park this year, so you can think of meatballs as four times as a court, i.e. being randomly issued. This is the pitcher who throws these most often:

Quick Note: XHR is just the sum of home run probability for every court thrown by a pitcher this year. The XHR/100 is expected to be every 100 pitch home runs, which will put everyone on a similar scale. You can take it broadly into account for every home run for beginners, as 100 pitches are the standard appearance length.

As you can see, this measure is very relevant to pitchers who are actually prone to home runs. Actually, I would be shocked if Tyler Anderson wasn’t on this list. Even in his most effective situation, he threw a large number of low-speed four-slit fastballs in the center of the strike zone. He hasn’t given up on overdose home runs for every fly ball or anything, but his court will cause a lot of swings, very few whips and a bunch of fly balls, and it’s a good year – in 2025, he’s tortured, and this list helps explain why.

Actually, I think the most interesting name here is the outlier: Clayton Kershaw. His 2025 season has been very strange so far: a career-low strikeout rate, a career-low strike rate, a career-low fastball speed… It’s also one of the lowest home runs in his career. The model will say his good home run fortune has not been obtained yet. I agree with this assessment – watching Kershaw’s start of the year lead me to say, “Boy, I think the pitch will be smashed” more than ever.

To be clear, throwing a lot of meatballs isn’t the worst thing you can do as a pitcher. None of these guys are elite choices, but they are almost impossible to play. Home runs may be the worst result, but you can throw worse balls. For example, a court that is always taken by the ball is bad. Even the most home run court can get quite a few foul balls, get easy balls, and so on. Humming a foot on the batsman’s head, or bounced in the dirt, is just the batsman’s free counting leverage, usually a free runner.

On the other side of the ledger, avoiding crushable pitches is only useful, only if the ball can be saved in the strike area to take advantage of your ability to suppress contact quality. That is, the pitcher who throws meatballs has a higher strikeout and walking rate. Avoid home runs the King this year? José Soriano threw 2,581 balls and only 11 meatballs. He hit only 21% of his opponents and he walked 10%, but stands out by four-player racers on the street when you run a huge ground ball rate and almost never bring your opponents jail-free cards.

Soriano has something in common with some of the other outstanding figures in this category because he gave a good sinking piece. Logan Webb is always outstanding in this skill. I have the lowest meatball rate in the top 10 every year. Cristopher Sánchez didn’t miss the top ten, second only to Webber last year. Abner Uribe (dominated by pendants) has the lowest meatball rate this season. Brendon Little (also a sedimenter) has the lowest XHR/100. Here’s another good sign: these guys are elites who avoid home runs, and our models label them as elites to avoid home runs.

Is this a bit like gi header statistics? certainly. I keep mentioning that pitching isn’t just about whether you give up on your home run. PitchingBot named Seth Lugo the worst starter in baseball this year, but in terms of expected home runs, he was smack dab in the middle of sales. The problem is that he is running Soriano’s unwavering strikeouts and walking numbers, but while throwing a lot of four shoes and knives. In other words, when you combine home runs with home runs, the extra obstacles and lack of freedom appearing can be significantly important.

However, I think the model output here is worth paying attention to. “That pitch looks dangerous” is an important eye test. I use it when I evaluate the pitcher and I would love to have a more stringent way of measuring. Meatball rate and XHR/100 are both done well in my opinion, so I’d be happy to add them to my consideration for any given launcher. Hey, so can you! Here is a list of every pitcher in this year’s baseball game (minimum 1,000 courts), and related pitcher home run estimators. Happy meatballs.