Brendon Little’s Big Question (for batsmen)

Few things can itch like baseball players. Blue Jays Reliever Brendon Little currently has this difference. Pick up Gander:

That was Ramón Laureano swaying on the little knuckle curve, which rarely bounces on the front edge of the plate. Here is another (Missing Matt Olsen cameo):

Sean Murphy quickly resigned to beat another curve in the dirt, which was Alejandro Kirk’s choice. There is another bike ride home:

It was the teenager Caminero who mimicked a curved bottle opener and rebounded curves, which should hardly be considered patented.

As Ryley Delaney pointed out a few weeks ago at Blue Jays Nation, the course is the most advanced product. It produced 30 whips in May and any court thrown by relief workers are tied together. It allowed the lowest contact rate this season (minimum throws 200 throws), which pushed the small climb swing strike rankings, where he was tall with the fourth-highest swing strike rate in the Grand Slam (minimum 20 innings). The course also has the lowest area rate (region %) and the highest waste rate for any personal product. Finally – I have to say I like him and this about him – rarely do two hits 83% of the time. Eighty-three percent. Five of six times! (All statistics are June 8.)

Opposing batsmen should When they hit two strikes, they rarely know what. This will be a knuckle curve because the pitch is stupid, even if it is not plagued. It is no Will enter the strike zone because it is not necessarily. Battery player Will be Anyway, it is usually in a non-delegated form Oooooops Swing, because there were two strikes, of course he was swinging. All of this is pre-scripted; even if the book is rare, it should be, and does not matter. After all, this is someone who knows that he uses the same trusted hammer whenever he displays with his nails, which is a totally good choice. This is someone who doesn’t need to pay attention to the theory of the game and its complexity, because he replaces it. This is a guy who is engaged in pranks. This is a man without goodness.

What about the court becoming so effective? I’ve been the idea that pitching doesn’t need to be a “good” to succeed. They can be simply unique and strange. The small knuckle curves are definitely in the latter category. The only track that it’s fairly close is Kyle Freeland’s curves—which are very similar in terms of overall induction of vertical and horizontal motion—but hardly makes his curves more difficult, while 500 cuts per minute from the higher arm slots. The result is a court that looks more firm, presumably hitting the area, just to drop the bottom and make the opponent’s batsman reflect on all the decisions he made in his life that have trapped him in an absolutely terrible hacking attack, who had just grabbed onto a shaky curve without reaching the plate.

…

STATCAST’s new bat tracking data is as exciting as many. The most obvious use case for these new measurements is better evaluation of batsmen. However, these data can tell us about the players on the other side of the ball (i.e. the pitcher) that I am not alone, which makes me forced even more immediately. While more obvious applications include providing better background for exit speed, launch angle and spray angle, Stephen Sutton-Brown Baseball prospectus The STECTPRO indicator and related pitch modeling work quickly determined the very clever use of swing path tilt:

The inclination relative to the mean inclination of the four seams in the middle, telling you where they expect to cross the plate ==>Model the expected plate position given the relative rotation position, giving us a way to verify the expected pitch probability

– Stephen Sutton-Brown (@srbrown70.bsky.social)2025-05-21T02:00:34.952Z

Sutton-Brown’s Sabermetric pursuits and achievements usually go on my salary level. I don’t know how to model the expected pitch probability! But his originality immediately shocked me, especially the premise of estimating the batsman’s expected field position based on the observed inclination of the swing. Going further, I think we can assume that a batsman will usually exhibit mechanical continuity from pitch to pitch. Therefore, his swing path should have a consistent inclination at any given pitch position. This assumption allows us to tilt the swing path at any pitch to “reversely engineer” the batsman’s expectations of the course position. Calculate the difference between the expected and the actual position and you will leave what I’m talking about the implicit distance or IMD.

This is an imperfect theory. On the one hand, assuming that the batsman is mechanically consistent on the swing, this may be most Right, but not always. Not all swings are good fluctuations (as mentioned above), and even some good fluctuations are different from others. For now, this assumption is it. These inconsistencies affect every batsman, so at least inconsistencies are consistent.

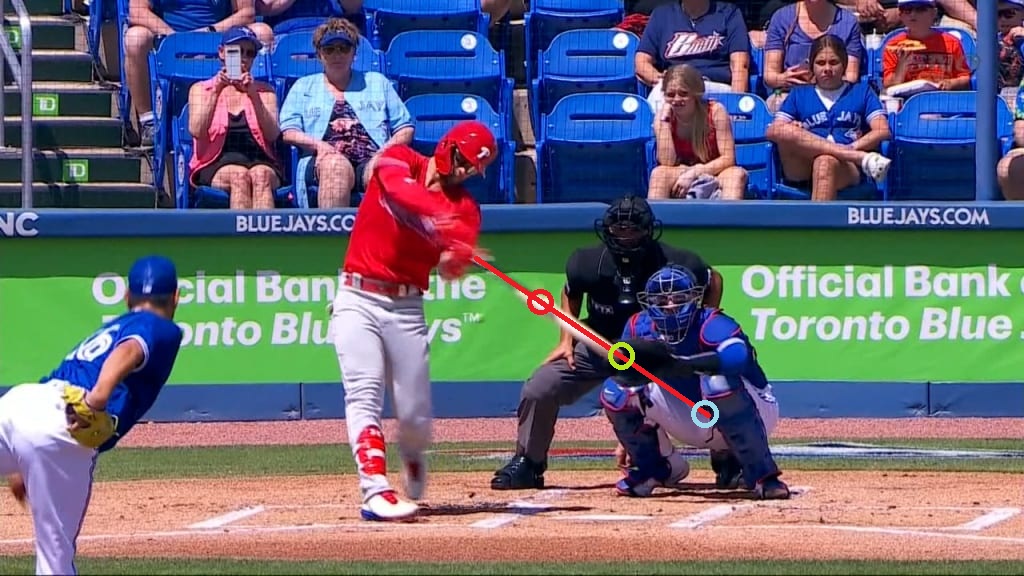

Let’s consider the still image of the swing where the bat is as flush as the home plate, just connected or waving to the court. If you draw a line from the knob through the head of a bat like a lightsaber, the rotation path will intersect the tilted position with the vertical and horizontal coordinates of the height change. Let’s take Bryce Harper as an example:

The red, green and blue circles are all effective pitch positions based on the inclination of the swing path of Harper. Statistically, I don’t have enough ability to determine whether Harper expects that pitch in his hands or down and left and right, both along the lightsaber’s tilted swing path. To solve this problem, I calculated the average swing path inclination for a batsman based solely on pitch height. The IMD then becomes an estimated value of the average implicit distance along the vertical plane (ie, the height relative to the pitch). By reducing this problem from two dimensions to one dimension, we simplify one question: “How far does the batsman swing distance exceed?”

This makes us the real reason why we’re gathering here today: the little knuckle curve, which, in addition to all its other honors and recognitions, has the largest average IMD (absolute terminology) of at least 200 throws this year. This is the only pitch that averages over eight inches of distance, not to mention nine inches. It’s not just smelling it! The batsman averaged three-quarters of his feet hit his knuckle curve Every swing. They just swing on the top of that suction cup:

2025 implied remote leader/lagged

Data current as of June 1

Minimum. Throw 200 balls

(First, this is not a Kodai Senga post, but Senga has three tones here – two leaders and a laggard – that is fascinating. Furthermore, since IMD is the basis of vertical motion based on vertical motion, we can see its bias against vertical motion, and the trend of vertical motion is unacceptable compared to later motion characteristics.

The size and orientation of the pitch IMD can tell us a lot about its effectiveness. For example, a course with a larger front IMD (meaning missing at the top of the court) causes a shallower launch angle and more ground balls, while a larger negative IMD (under the court) tone causes a steeper launch angle and more popups. (“Start Angle Effect” the following individual trends controlling pitch and opposite hitters.) The line doesn’t pass the origin perfectly, but it’s very close and can be severely affected by survival bias:

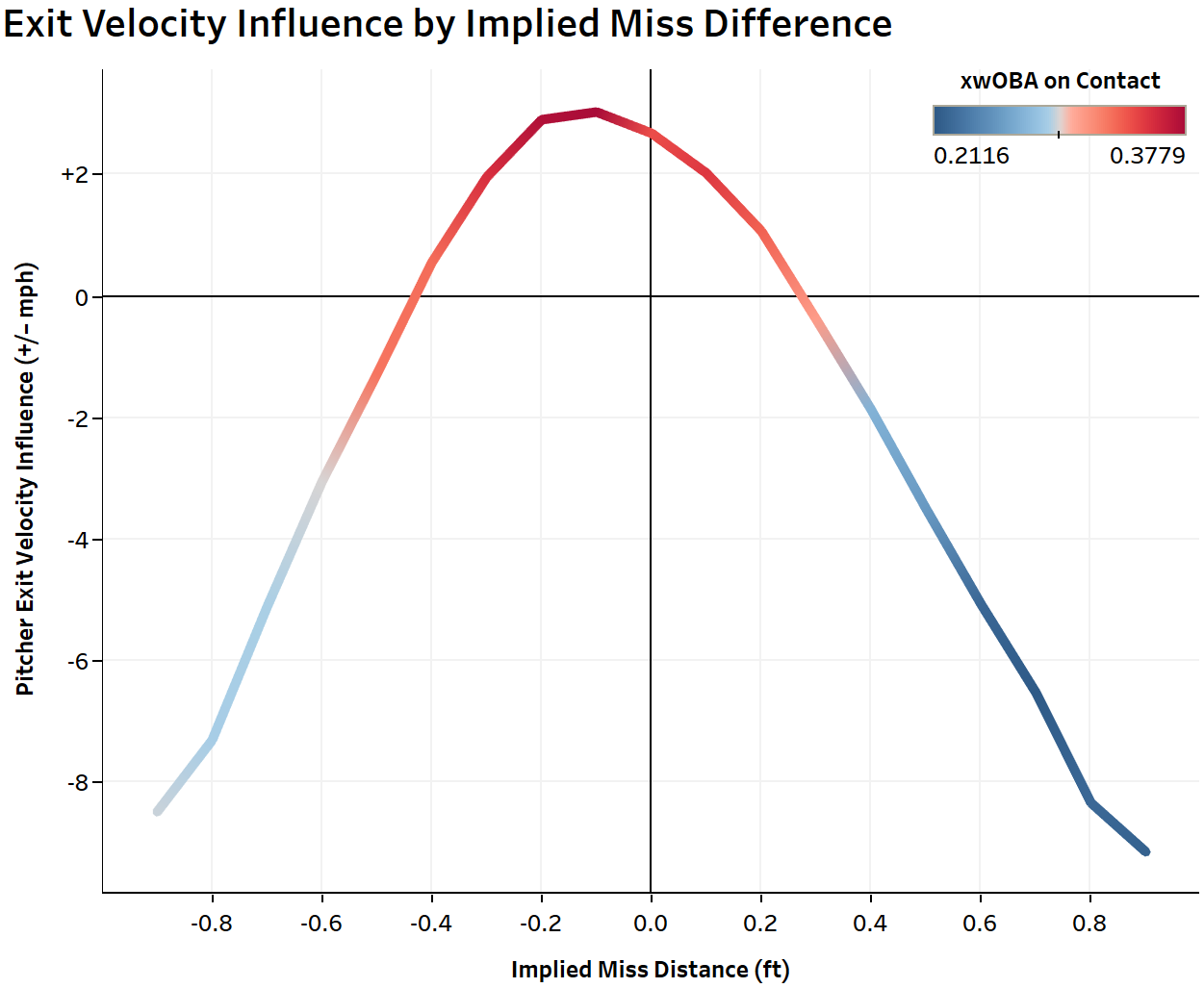

The absolute amplitude of the IMD is also related to the lower exit velocity. (“Exit Speed Effect” controls pitch speed and the personal trend of the opposite batsman.) This is convenient for my theory and my fragile self, and like the start angle effect above, batsmen do maximize their exit speed because they really have an effective pitch for the hint distance, which is effectively zero…effectively zero…

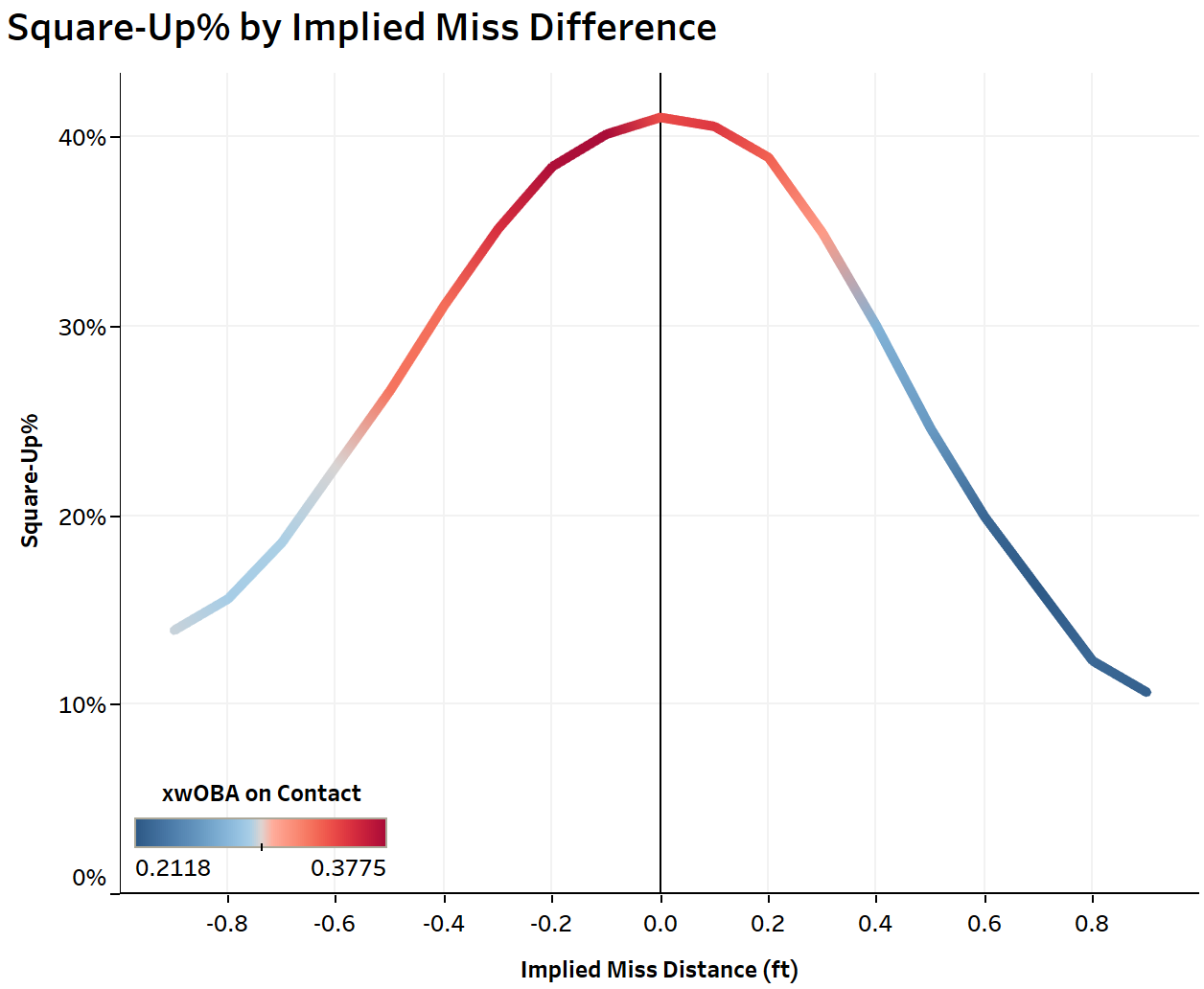

…because if IMD is zero, then the chances of a batsman are very likely to fail:

From the color-coding in each graph, you can see from pretty much every vantage point how expected contact quality (vis-à-vis weighed on-base average on contact, aka xwOBAcon) is maximized where IMD is minimized, and how pitchers’ abilities to exert their influence over outputs — by suppressing exit velocities, by skewing launch angles, by preventing flush contact — can be externally validated.Number of knuckle curves: -2.1 mph’s exit velocity effect, -10.4 degree start angle effect, 13.3% square % (average league 31%), .171 Xwobacon (compared with the actual Wobacon of .347). This is all track.

So I think of IMD almost as a measure of pitch swing (missed) quality. Not only does it help confirm things like the swing strike rate, it also provides authenticity for the pitcher’s connection management skills and how well it performs. The pitch positions themselves have already gone a long way to explain these positions. The position paired with IMD increases clarity. IMD may require further stress testing – for example, the swing path inclination does not increase linearly with pitch height compared to pitch with high targets, so IMD may be exaggerated by IMD (such as lower targets or little knuckle curves), such as four seamers, but this countertop version seems to be enough to illuminate me.

Ultimately, IMD is just a descriptive indicator. It tells us what happened (or at least gives us our own version of the story about what happened), and may have some predictive value for it, but no explanation Why The little knuckle curve is so good. Why It caused such a tragic swing, just Do. I think this is the work of Sutton Brown and like-minded nerds (free) who have pursued these answers through modeling of capital, through shape imitation, tunneling and sequencing, etc., through modeling of capital, Arsenal interaction effects. These topics can always provide an explanation for Little’s dominance. (Talk about which, stuff + like the tone in question.)

Nevertheless, it seems pretty in terms of descriptive indicators, especially when it confirms my little king, which I quickly became extremely interested in. Little’s Knuckle-Curve makes the batsman look like absolute Buffoons, and IMD confirms that. (Editor at the beginning of this post? I chose them by looking for the three largest IMDs caused by the little knuckle curve. They didn’t disappoint them. It almost never competed for competition when it reached the plate, which added to the insult of the injury. He couldn’t continue to get rid of it. IMD suggested he might.