José Soriano

On any given court, swinging is definitely the best result for a pitcher. The ball doesn’t work, and the number of times supports the pitcher, and the batsman may look a little stupid in the process. It is reasonable to think that a pitcher with multiple pitches may also have a strong strikeout rate with an above-average pitch rate. Then there is another group of smaller pitchers who have multiple pitches with elite pitching rates. These rare shots will certainly have the best strikeout rate in baseball, right? Of all the starting pitchers this season, only eight players have multiple pitches, which take more than 40% of the time.

Pitcher with something swaying

Mackenzie Gore leads with three weapons missing from elite bats, followed by some of the best strikeout artists in the game. At the bottom, though, are two pitchers who have strikeout rates that are much lower than expected because they can create a trend: ground ball experts José Soriano and Rookie Cade Horton. (By the way, Horton’s change is the third highest WIF rate for at least 100 pitches this year, but his strikeout rate is 17.6%.

What if you lower your threshold to a high rate threshold north of 30%? There are 18 starters, three or more of these inefficient but impressive courses. Spoiler: Soriano appears again.

Pitcher with something swaying

Here we see more of the best strikeout pitchers in baseball. Soriano is a part of the outlier along with rookie Noah Cameron, struggling Tanner Bibee and crafty veteran Michael Wacha. In most cases, if your pitch mixture contains multiple pitches that can improve climax rates, you may see high strikeout efficiency. This makes Soriano a particularly obvious outlier.

A month ago, Michael Baumann investigated curious cases of high-speed pitchers on the Angels and their more than expected strikeout rate. Jack Kochanovicz and Soriano are presented in this post, examples of people with above average, who can’t remove anyone, but the latter actually owns weapons the former doesn’t really own the bat missed. This requires further investigation.

The first thing you should know about Soriano is that he leads the ground ball with a considerable advantage. His 67.6% ground ball is 6 percentage points higher than next pitcher Andre Pallante and nearly 8 percentage points higher than last year’s position. He has just recently set a single game record for Earthball. All of this seems to be designed as he increased the use of the sinker by four percentage points this year, and now it accounts for more than half of his pitch.

“I like to throw away my sinking pieces because they get into the situation faster,” Soriano said in an interview with Jeff Fletcher in April. Orange County Register. “I would rather do this than have more courts and more strikeouts.” Currently, he averages 3.79 goals per set, ranking 17th out of 59 qualified starters. His approach is to work quickly through the lineup, creating a lot of contact with his hard sinker on the ground and pushing his secondary ball into a secondary option.

The simple answer is that the batter simply doesn’t see Soriano’s court enough to allow him to get the total number of strikeouts. They threw the ball into the game before they could strike and send it back to the canoe. There were two strikes in all the stadiums in the Grand Slam, and only 26.7% of the stadiums in Soriano were in this case. He didn’t give himself enough chance to strike out the total.

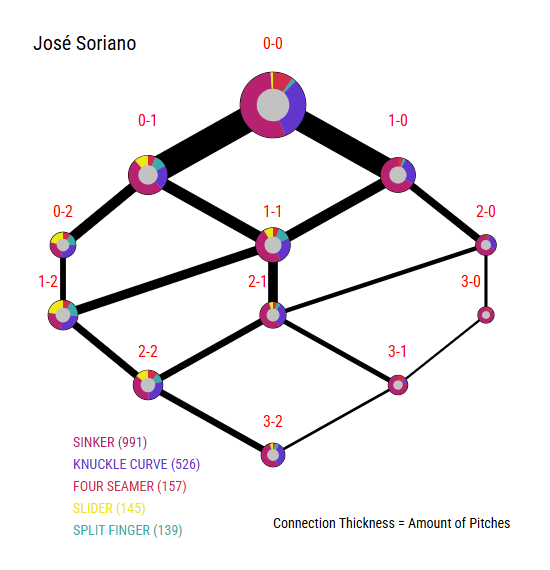

But what happens when Soriano takes two strikes? Here is a pitch mix that he didn’t have two strikes, and how he changed after he got there, and a web diagram showing how he used in each count.

José Soriano

| Pitch Type | Usage before two strikes | Used with two strikes |

|---|---|---|

| Sedimentation tablet | 56.8% | 33.5% |

| Curve ball | 26.2% | 28.7% |

| Four people | 7.7% | 8.8% |

| slider | 4.1% | 16.5% |

| Separator | 5.2% | 12.5% |

As you can see, Soriano was good for his pendant early in the quantity, but began to sprinkle the separator in his slider and two strikes. His three non-fists combined for his three strikes of just 57.7%, so even if the count decided to try to get a swing, he still relied on his hard work, over 40%.

It’s one thing to get the chance to use the secondary pitch, but did he use them effectively when he throws them? Here are some basic board discipline indicators by pitch type.

José Soriano, Discipline of Plate

| Pitch Type | district% | Two-hit zone % | swing% | % of two-strike swing | What % | Two gusts of wind |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sedimentation tablet | 57.7% | 52.6% | 49.3% | 65.7% | 17.3% | 16.5% |

| Curve ball | 44.9% | 38.0% | 35.9% | 60.7% | 42.3% | 35.2% |

| Four people | 54.8% | 50.0% | 41.4% | 65.2% | 25.8% | 23.3% |

| slider | 32.4% | 36.0% | 55.2% | 60.5% | 43.8% | 40.4% |

| Separator | 24.5% | 15.4% | 43.9% | 38.5% | 35.5% | 32.0% |

The biggest takeaway from that big table is that once the count reaches two strikes, the batsman of each of his course types swings more frequently in each of his course types, but in these swings, the batsman squanders less frequently than in the early stages of the count.

It’s easy to parse what happened in his splitter. He wouldn’t throw it into the area, and his two strikes were even less. Some of these may be intentional, as pitchers usually use their segmented batsman to chase the batsman, especially with two strikes. But it’s obvious that he has a hard time commanding that tone when you look at the place where he’s missing. One third of his two-strike splitter ends in an easily absorbable position that defines it as a waste area. He completely won a swing, one of the wasted split balls.

Figuring out what happened with his curveball, he threw curveball more frequently than any non-fast ball and was very effective before both strikes. Interestingly, his curvy ball’s stuff + level dropped to 73 this season, down from 104 in 2024. Given that the opponent’s performance is better than last year’s .270 WOBA/.251 XWOBA XWOBA, 2025 2025; .300 Woba/.262 XWOBA, it’s hard to determine why the model is sore on the court. Perhaps the model is collecting ways in which his curves interact with his other arsenals.

His curve ball sticks out from the rest of the tracks as you look at his release point data. Its vertical release point is two inches taller than his pendant, and the horizontal release point has a three-inch difference. The release angle on the curve ball is also about six degrees higher than his pendant. These differences are small, but they may be enough for the batsman to detect when throwing. The curve is annoying enough to produce an elite gust alone – its speed at 93% of the pitch type, with a level breaking far above average – but as the batsmen suffered two strikes, perhaps this slight release difference is enough to make them more stereotyped.

Soriano was obviously comfortable using his sinker as a staggering force for two strikes, even if that meant fewer strikeouts. It seems that this is an intentional approach that values quick work and ground balls rather than actively looking for whifs. It is important to note that Angels currently have the worst defense, with each OAA baseball, whose infield ranks 27th in the same metric. This approach is very focused on allowing contact, whether or not hesitated to the ground, which seems like a bad decision, given his defense behind him. That’s why his BABIP allowed .317 this year, and his era was almost half higher than his FIP.

I think that simply throwing his secondary ball often solves all his problems. He obviously had a hard time finding his separator, and his curveball had an issue with that release point, which stemmed from his mechanics rather than his method. His slider seems to be the only minor pitch that keeps its validity, regardless of whether he throws it. I do think that winning more whips with his breaking ball might be a better way to go than relying on the poor defense behind him. Even with their problems, his playing ball still has an elite whip rate, which is a pity that he has not made the most of these weapons.