How to pull the ball to the opposite side

Yesterday, I wrote an introduction to STATCAST's latest round of bat tracking metrics. Mike Petriello of MLB.com wrote a real primer, so I tried to analyze different metrics by analyzing how different metrics use several common tone types. We're still figuring out how to use these new toys, but today, I want to explain how my first entry into the bat tracking metric made me a specific player who did some weirdness, which gave me some little stuff about how to spin. After all, that's why we're exploring all these weird new numbers here first.

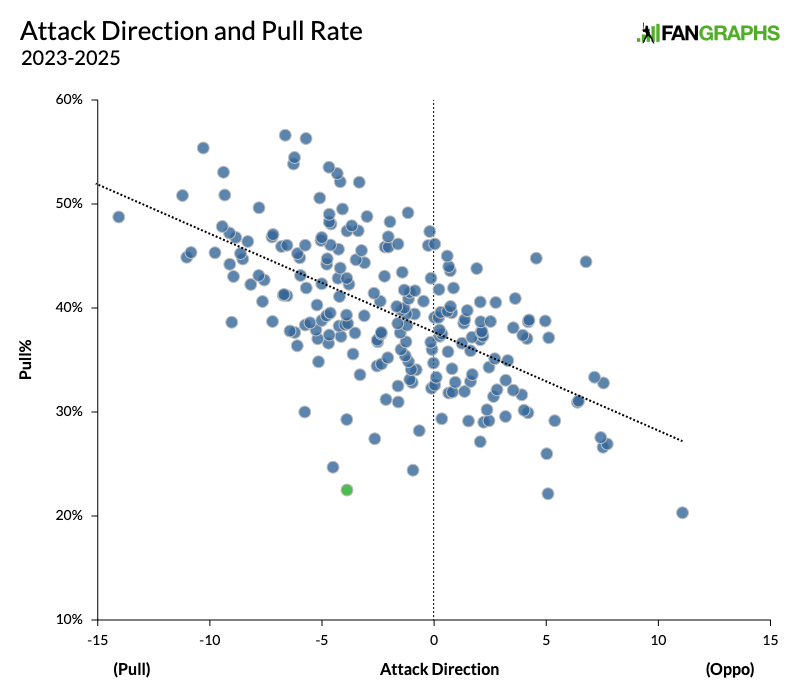

In the first photo of playing the game with the metrics, I tried to build something simple. I picked up the entire BAT tracking data for all qualified players and I focused on the attack direction, which tells you the horizontal angle of the bat when it comes into contact (or the moment when the bat is closest to the ball when it is breathing). It seems simple to me. Like most bat tracking metrics, it is also an indicator of timing and location. Usually, you need to hit the inside court further before the plate. If you are behind the court, your bat will tilt to the opposite court and you will not pull the ball. If you are in front of the court, your bat will tilt towards the side of the pull and you will pull it. The average attack direction of the player should be related to their pull rate, and the numbers are almost resolved. The correlation coefficient between the attack direction and the pull rate is .60:

Most points gather around very clear trend lines. As you would expect, players who have the ball more tend to turn the bat toward the pulling side. What I'm interested in is the green dot at the bottom. It belongs to Leody Taveras. I guess yes Leody Taveras, if we really believe in our own charts, we probably should be on this particular website.

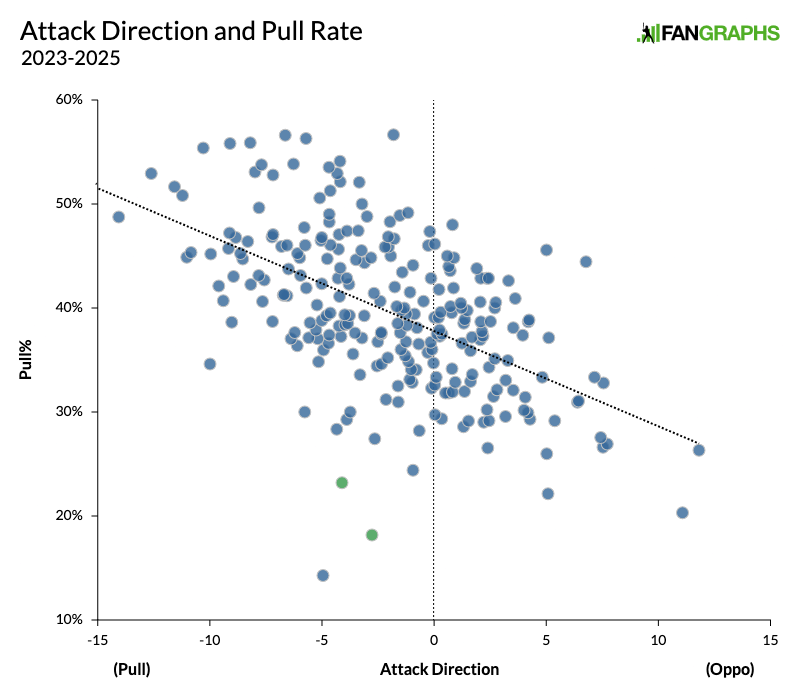

Taveras has a medium-low attack direction and four degrees from pull, but he has the third lowest pull rate for all players on this chart. I couldn't help but wonder how he did it. Before I delved into it, I was reminded that the fact that he was a turnover might have something to do with it. So I extracted the data again, this time I shook hands apart. On the image below, the switch catcher will appear twice:

The correlation is not that strong, as now split the switch fishermen into two different players, with two smaller samples (this is how Patrick Bailey, the right-handed, right-handed, sampled Way at the bottom). But now there are two green dots! They are all Leody Taveras! From both sides of the plate, Tavelas looks like his pull rate should be above average, but rather one of the lowest pull rates in the game. At this point, I was formally curious, so I started looking around.

First, I specifically studied the attack direction of the ball against the opposite field. Since the start of tracking the Bats midway through the 2023 season, when Tavelas hits the ball in another way, his average offense direction is three degrees in the opposite territory. The average offensive direction of only four players in baseball lowers the opposite area. Strangely, they are all dull people. Salvador Perez, Yordan Alvarez, Aaron Judge and José Ramírez are all in two degrees towards the relative field, with Austin Riley tied for three degrees with Taveras. Taveras is definitely not sl. He is no different from these five guys. So when he goes the opposite way, he is not only doing a different way from most batsmen, but also a completely different swing from the only player on that ledge. He is indeed a little strange.

Next, I try to specifically look for balls that hit the opposite field, even if the bat is currently facing the pulling side. Only 21% of the balls hit the opposite ball, and the bats tilted completely toward the pulling side. I did a baseball Savant search and set the minimum attack direction to 7 degrees to the pulling side. Since the start of the BAT tracking, 5.5% of Taveras' hits fall into this category. There were at least 200 BIP players in the period, which was the 11th highest rate. Elehuris Montero is the champion with a shocking 10.5% title, but no player plays the same speed as he does in Taveras's game.

At that time, I decided to look at individual balls that fall into this category: even the balls that are tilted when the bat is touching will enter the balls that are opposite. How exactly does this happen? Try to imagine it in your mind. If the bat tilts toward the pulling side and it rotates in that direction anyway, how does the ball eventually develop in the opposite direction? There are two main answers. This is a less common method:

That's Taveras' way, stepping out in front of the curveball and hitting it off the end of the bat. He brought it up so perfectly that if the end of the bat was pulled out, the ball might have fallen into it. So, this is a way. In fact, even if the attack direction is 7 degrees or above on the pull side, we still hit 21% of the balls in the relative field, but the screaming hit the end of the bat at 80 mph. That's a way.

Another way is more common, it looks like this:

In those same balls, even if the pulling force in the attack direction is 7 degrees or more, 50% is classified as a pop-up, while 65% is above 38 degrees. Basically, when you hit the ball in that weird way, it's almost always a prompt shot or a pop-up. Leody Taveras taught me.

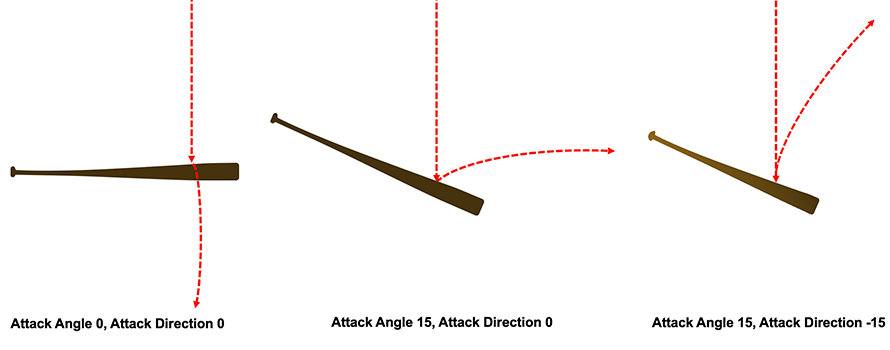

This is related to the angle of attack. If your bat is completely parallel to the ground but tilts toward the pulling side, it is almost impossible to hit the ball the other way around. However, when you pop the ball out, you don't hit it. You are in trouble. No matter what the situation is, your bat will almost never be parallel to the ground. According to Statcast, bats lean down on over 80% of swings. If you only look at popups, that number is above 90%. About half of the pop-ups appear on four shoemakers and cutting machines, where it's hard for the batsmen to catch up with the court and swing under the court. The rest are softer things, and these courses are usually very low in the area. I need you to do some 3D visualization here, because my graph is not very good:

On the left is a perfect bat, parallel to the front of the plate. Now, imagine you tilt the bat downwards and just under the ball. If your bat leans towards the opposite field, or directly towards the central field like in the middle example, you might just get the ball dirty from behind you or on the field stand opposite. However, once it is tilted toward the side of the pull, it can remain fair, bounce upward and towards the opposite field. Imagine that the bat on the right looks stylish because it has been predicted, pointing out first baseman. Taveras can show us what it looks like in the real world:

If his offense is zero, he will pollute the ball and foul the ball along the shelf of the third baseline. He only keeps fair because of his 18-degree offensive direction.

Look, I don't have big takeaway here. I just thought it was interesting. I think this highlights the angle of the bat even the most mundane way of hitting the ball. If you asked me yesterday if you could take the opposite approach when your bat is heading to the pulling side, I have to think about it, but my first reaction was rejection. Bats and balls move in space so quickly that it's hard to track, but bat tracking metrics help explain why Taveras pops up so frequently so often and how they can hit the ball in the first place.