How important are trail runners? investigation

Watch this drama. What did you notice?

Here’s what I’ve seen: Lee Loft, a soft fly ball 248 feet from home plate. Chandler Simpson circled it, but it lost some motivation when it landed in the glove. Twin third base coach Tommy Watkins sent out non-temporary Trevor Larnach (level 18th sprint speed). Light ball, slow runner, close-up game on the plate – Lanach slides in front of throwing. It’s an exciting sequence and I missed a big part of it.

In a speech past two Saturdays at the Saberseminar conference, Josh Kalk, assistant general manager of the Minnesota Twins, participated in the same exercise, showing Lee’s sacrifice flies, and then asked the audience: What did you notice? He wanted to talk about the drama behind it. Specifically, he wants to talk about this person:

That was Carlos Correa, reading the throw and sneaking to the second base. Kalke suggests whether the team takes advantage of these cross-country opportunities is more important than most people realize.

There is a perfect post idea. How often does the team take advantage of potential trail runners to advance? Which teams are the best? What impact are we talking about here?

I think the differences between teams are trivial at best. Even in the broadest sense, the base margin is slim. On the Statcast’s Baserunning Run Value rankings, the difference between the best team (winemakers) and the worst (Rocks) is 20 runs, or about 2 wins. (Our similar BSR statistics treat the gap as roughly the same.) Baserunning is an ugly duckling for public baseball analysis compared to hitting, pitching and even field battles, and I think the narrow differences between teams help explain why.

Another reason: Many changes between these teams can be explained by a distinct variable. Overall, fast teams are often good foundation teams. For example, BSR’s leading winemaker is also the fastest team in the Grand Slam. The relationship between Sprint Speed and Baserunning values is relatively strong – since the Dawn of Statcast ERA (2015), the R square between Team Sprint speed and Fangrend Sprint Speed is 0.307, with Fangraphs BSR and Statcast Baserunning values:

However, even if considered at sprint speed, there is still a large part of the difference to be addressed. Take the poor Rockies. Their sprint speed is the same as the brewer. They also rank last in BSR and Baserunning Run values. As Juan Soto and Josh Naylor have shown this season, speed isn’t everything about running the base with skill. It requires instinct, good reading, second decisions and high-quality coaches in the corner. It’s more than just the scaling of the dock.

From Lede, the slow-footed Correa advanced to second when throwing. There is a crucial part of the play where Correa must decide to take a break in the finals, or stay first. It was here that third baseman teenager Caminello had to make the same difficult split decision:

If Caminero cuts off the throw and Correa hangs out on land without people, it’s the end of the game. But he moved the gloves at the last second and let the throwing sail go home. Given how close the game is on the plate, I think Caminero made the right call. But maybe even better is Correa’s reading – Caminero is in perfect position, and Correa manages to take the foundation anyway.

Not all trail runner scenarios are complicated. Sometimes even the most oafishners can rank second. If you are doing offshore on OAFs mainly, you want all teams to show roughly the same skill level. But that’s not the case.

To collect my data, I rely on the wisdom of the official scorer. There is no easy way to think about trail runners, because I have learned quite painfully over the past few weeks. Baseball Savant provides .CSV files for each pitch in the regular season (vote Savant), but the data does not contain much basic information in tabular form – only if the runner starts, in fact when the runner starts, and the identity of the runner. The R function produces the basic state of the given drama that comes with it (thanks to Robert Frey for pointing it out), but there is no way to determine if the runner gets there a second time because he hits a double or because he hits a single as a trail running and becomes second on the track.

It also requires a clear definition of who exactly defines it as a “cross-road runner”. First, I eliminated all home runs (apparently), triple (because triple will always clear the base and the batsman can’t score without errors) and ground balls (different situations). This makes all singles and doubles at least one runner on the base, and all the fly balls with at least two runners at the base, which is possible for a trail runner.

For singles and doubles, I made a controversial decision to call the batsman a cross country runner in all cases. My logic is: If someone hits the middle with a runner around the corner, the third person will easily score in 99% of cases. He is no longer the defense’s attention. First, it’s the guy who becomes the lead runner, and the defender focuses on preventing his progress and making the batsman a trail runner.

The logic of flight is somewhat different. If there are multiple runners on the base, I define a trail runner as the runner that is furthest from home plate. For example, if the base is loaded, the trail runner will be at the first base. However, in all cases, I limit the number of possible trail runners in a given race to one.

To determine these situations, I used the GameDay description. If GameDay’s description says the runner plays singles and then advances to second, I think he’s a trail runner. (An example: “Roman Anthony singles on the ground ball, midfielder Jung Hoo Lee. Flying balls are a bit tricky. If the name of the Trail Runner appears anywhere in the description, I think of it as a Trail Runner Advance. (If the runner stays, it won’t mention it; if they raise the base or get thrown away, they will appear in the description, and I removed the double playback from the dataset.)

As of August 25, by these defined parameters, there were only 501 trail runners improving throughout the season. (I admit, that surprised me.) So, which teams do the best? How important is this? First, I calculated the total number of progress for each team. Here is the list:

Cross-country runners progress

| team | Cross-country runners progress |

|---|---|

| Detroit Tiger | 28 |

| St. Louis Cardinals | 26 |

| Toronto Blue Jays | 25 |

| Miami Marlin | twenty three |

| Arizona Rattlesnake | twenty three |

| Milwaukee Brewers | twenty two |

| Cincinnati Reds | twenty one |

| San Diego Priest | 20 |

| Tampa Bay Light | 20 |

| Chicago Bear | 19 |

| Boston Red Socks | 18 |

| Los Angeles Dodgers | 18 |

| Cleveland Guardian | 18 |

| San Francisco Giant | 18 |

| Kansas City Royals | 17 |

| Philadelphia Philadelphia | 16 |

| Baltimore Orioles | 16 |

| Texas Rangers | 15 |

| Colorado Rockies | 15 |

| Pirates in Pittsburgh | 15 |

| Chicago White Sox | 14 |

| New York Metropolis | 14 |

| New York Yankees | 13 |

| Houston Astronauts | 12 |

| sports | 11 |

| Angel of Los Angeles | 11 |

| Washington National | 10 |

| Minnesota twins | 9 |

| Seattle sailors | 9 |

| Atlanta Warriors | 5 |

Source: Baseball Savant

However, not all progress is equal. The runner did not get out of third place, improving running expectations over the runners with two outs. To figure out the value of each progress, I calculated the run expectation for each base state after the game, and then traced back to calculate the expected value if the Trail Runner is not advanced. The delta between these two numbers produces rough running values. Put all your running expectations together and you will have a running value ranking similar to Trail runners. This is the look:

Cross-country runners run to get

| team | Obtained |

|---|---|

| Detroit Tiger | 3.786 |

| St. Louis Cardinals | 3.474 |

| Arizona Rattlesnake | 3.353 |

| Toronto Blue Jays | 3.327 |

| Cincinnati Reds | 3.271 |

| Boston Red Socks | 3.05 |

| Miami Marlin | 3.039 |

| Milwaukee Brewers | 2.934 |

| Kansas City Royals | 2.907 |

| Philadelphia Philadelphia | 2.898 |

| Chicago Bear | 2.856 |

| San Diego Priest | 2.739 |

| Tampa Bay Light | 2.736 |

| Los Angeles Dodgers | 2.609 |

| Baltimore Orioles | 2.317 |

| San Francisco Giant | 2.189 |

| Chicago White Sox | 2.157 |

| New York Metropolis | 2.035 |

| Cleveland Guardian | 1.981 |

| Pirates in Pittsburgh | 1.973 |

| Texas Rangers | 1.948 |

| Houston Astronauts | 1.875 |

| New York Yankees | 1.774 |

| Colorado Rockies | 1.774 |

| sports | 1.429 |

| Washington National | 1.351 |

| Angel of Los Angeles | 1.195 |

| Seattle sailors | 1.023 |

| Minnesota twins | 0.947 |

| Atlanta Warriors | 0.657 |

Source: Baseball Savant

If Trail Notner does not make progress, it is based on expectations and running expectations in the delta.

Maybe this is a little overwhelmed. The gap between the Tiger and the Brave (more than three games) is not particularly spectacular. But this may be the wrong shot. In an ideal world, this is not a running expectation delta, but a victory expectation delta. The change in the expected points of victory illustrates more about the essence of Kalk’s comment: there can be a lot of importance for runners to move forward at a given level of competition and game.

Calculating expected changes in victory at a race level is complex – perhaps the task of the next article – but we can look at a representative example to show the potential impact of cross-country runner progress on victory. In late August, two American League wildcard contenders were locked in a fierce game. Rangers lag behind guardians. The swift Wyatt Langford stood at second base. On the first court, Corey Seager drove a clean line to the midfield. Guardian midfielder Angel Martínez made a huge throw, almost knocking Langford out:

If Tom Tango’s expected spreadsheet says if Seager is still in first place after this throw, the Rangers have a 70.8% chance of winning the game. Instead, he wisely tracked the throws (eventually not that hard, eventually – Martínez introduced this) and increased his team’s chances of winning by 10 percentage points. Since the runners are second and are not out, the Rangers have an 80.7% chance of winning at this point. Seager scored on the next court, and Joc Pederson jogged home after doubled the gap.

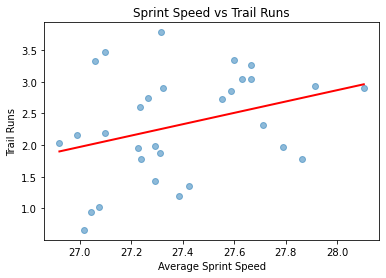

Strangely, “Runs Obtained from Cross Country Runners” doesn’t seem to be mapped neatly to the team’s sprint speed as against BSR. The R square between these two variables is only 0.11, which is weaker than the relationship that Sprint Speed had to BSR in the Statcast era:

Perhaps this explains why Kalk’s attention is focused on this edge part of the surface. There is no need for a set of Trea Truners to rank first on the Trail Runner rankings. Any team can pay a few extra times over the course of a season, or even swing the results of a few games – and pay attention to these free bases appropriately. When competitive edges are few and between each other, a penny on the sidewalk looks like a $20 bill.